Identifier Naming Convention

In this article, we present the identifier naming convention used in a growing portion of our How-To articles. It is presented as a motivated choice; we share the considerations that lead us to making this choice. Perhaps these considerations will help you to make an informed choice for the identifier naming convention you want to use (if any). Perhaps it even convinces you to follow the same convention.

The purpose of a naming convention

Decision Support applications are based on models. As you know, such models are a description of selected portions of reality. Nobody seriously disputes that having clear and descriptive identifier names help relating the models to the reality being modeled.

There are several use cases for developing with AIMMS:

The first use case of the AIMMS Language is to formulate models for Decision Support applications.

A second second use case of the AIMMS Language is to create generic libraries, for instance the libraries as presented in the AIMMS Library Repository.

The choices made in this article focus on the first purpose.

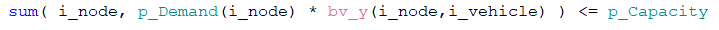

Particular to Decision Support applications are constraint definitions. Consider the following simple equality:

where:

symbol |

interpretation |

|---|---|

\(p\) |

price |

\(q\) |

quantity |

\(r\) |

return |

When values for two of these symbols are known, then the value for the third symbol follows, barring special cases such as \(p=0 \wedge r\neq 0\).

The impact of such an equation for the complexity of the model depends on whether values are already known for the symbols or not. To be concrete:

when the value of \(p\) is fixed, the equation becomes a linear equation. When all other constraints in the model are also linear, the total model is linear.

when the value of all three symbols are not known, the equation becomes a quadratic equation. When all other constraints in the model are linear, the model is still a quadratic model.

The complexity of the model (linear, quadratic, non-linear, with or without integrality restrictions), in turn, determines which solution algorithm can be used to solve the mathematical problem that is inside the model.

In other words, as a model builder, inspecting and analyzing a model, you will need to understand which of symbols used in the constraints are:

So-called knowns; values for these symbols are not determined by the solution algorithm but are directly, or indirectly, provided by an external source. Such symbols are usually called ‘data’ or ‘parameters’ in the operations research literature. In economic literature, these symbols correspond to so-called exogenous variables. These knowns are called

parametersin the AIMMS Language.So-called unknowns; values for these symbols are determined by the solution algorithm. They typically correspond to the decisions made by the decision-maker. Such symbols are usually called decision variables in the operations research literature or variables for short. In economic literature, these correspond to so-called endogenous variables. These unknowns are called

variablesin the AIMMS Language.

Distinguishing parameters and variables

The classical approach is to use prefixes. More modern approaches rely on the development environment to make such a distinction, for instance by:

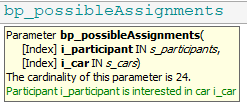

Hovering: hovering over an identifier shows a tooltip with typing and other detail about the identifier.

Syntax coloring: color an identifier based on its type, see also Configuring AIMMS IDE which provides a tasteful coloring scheme distinguishing parameters (

darkcyan) from variables (palevioletred).

These two modern approaches are supported by the AIMMS IDE. However, AIMMS models are not only presented in the AIMMS IDE, they are also part of other documentation for instance these How-To articles, in educational material, and in technical reports about the applications.

Note that the AIMMS IDE approach and the prefixing approach to distinguish between parameters and variables do not exclude each other, they complement each other.

Other naming conventions in practice

There are various alternatives:

camelCase An identifier is named starting with a lower case letter, and if several words are used, each subsequent word is started with a capital. for instance

priceIncrease.PascalCase A variation whereby the first word starts with a capital, for instance

PriceIncreasesnake_case Words are same case (mostly lower case) and separated by

_, for instanceprice_increase

There is no commonly accepted best way to present concepts in the real world as identifier names in a model.

Identifier parts and their purpose

As discussed, there are two parts of an identifier name, and these two parts have a rather different purpose:

The prefix: The purpose is to present the type, especially when it is a parameter or a variable.

The base: The purpose is to communicate the interpretation in the modeled world.

Our choice

In view of the considerations above, the following choice is made for AIMMS identifiers that are used in How-To articles:

Consider the example p_priceIncrease:

The prefix is the

pindicating that this identifier is a parameter. The prefixes are in lower case.The base is

priceIncrease, indicating that this is a change in price in the modelled world. The base is presented in camelCase.Because of the difference in purpose, the prefix is visually separated from the base by an

_.

Prefixes used

The prefixes encouraged are enumerated in the table below:

prefix |

identifier type |

|---|---|

s |

set |

h |

horizon |

cal |

calendar |

i |

index |

p |

parameter |

bp |

binary parameter |

ep |

element parameter |

sp |

string parameter |

up |

unit parameter |

v |

variable |

ev |

element variable |

bv |

binary variable |

cv |

complementarity variable |

c |

constraint |

uc |

uncertainty constraint |

n |

node |

a |

arc |

as |

assertion |

ac |

activity |

r |

resource |

mp |

mathematical program |

m |

macro |

qnt |

quantity |

cnv |

convention |

f |

file |

db |

database |

dbpr |

database procedure |

pr |

procedure |

fnc |

function |

epr |

external procedure |

efnc |

external function |