Solve with Lazy Constraints

The famous Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP) deals with the following problem: given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, a salesman has to find the shortest possible route to visit each city exactly once while returning to the origin city. One way to formulate the TSP is as follows:

min sum( (i,j), c(i,j)*x(i,j) )

(1) s.t. sum( i, x(i,j) + x(j,i) ) = 1 for all j

x(i,j) binary for all i > j

Here \(x(i,j)\) equals 1 if the route from city \(i\) to city \(j\) is in the tour, and 0 otherwise. Note that this is the formulation for the symmetric TSP in which the distance from \(i\) to \(j\) equals the distance from \(j\) to \(i\). This formulation is not complete as it allows for subtours. One way to exclude these subtours is by using subtour elimination constraints (SECs for short):

sum( (i,j) | i in S and not j in S, x(i,j) + x(j,i) ) >= 2 for all S, 1 < |S| < n

Here \(S\) is a subset of cities while \(n\) denotes the number of cities. This SEC enforces that at least one route is going from a city in set \(S\) to a city outside \(S\).

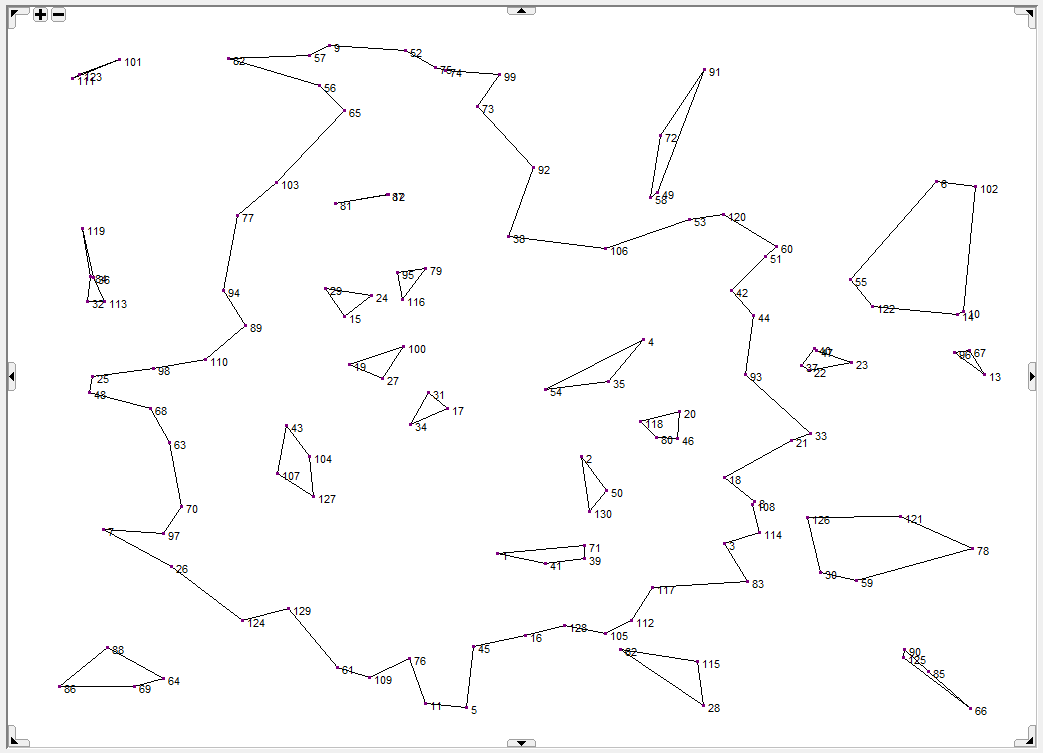

Fig. 19 First solution with subtours for instance ch130

The problem with the SECs is that the number of these constraints is exponential in the number of cities. For a TSP with 50 cities the number of SECs exceeds \(10^{15}\). Generating all SECs is therefore impossible.

Fortunately, we can use SECs as lazy constraints. Unlike normal constraints, lazy constraints are not generated upfront. Instead, they are only generated when needed. Typically lazy constraints are unlikely to be violated. In a TSP with 50 cities usually at most 100 SECs will be “active” which is only a fraction of the total number of SECs. Lazy constraints are supported by CPLEX and Gurobi.

The new AIMMS example TSP,

which can be found in examples, uses the above formulation. The SECs are added as lazy constraints inside a callback.

This callback is called whenever the solver finds a new candidate incumbent solution, i.e., a solution that satisfies formulation (1)

plus the SECs that have been added before as lazy constraints. The callback procedure checks whether the candidate solution forms one tour.

If it does, the solver found a true solution for the TSP and the solution is accepted; otherwise a SEC is added for each subtour.

Finding a violated SEC, the so-called separation problem, can be solved in polynomial time despite the exponential number of SECs.

The separation algorithm implemented in this example (inside the procedure DetermineSubtours) has a worst-case running time of \(O(n^2)\).

The example comes with several symmetric instances from TSPLIB. More information on the TSP can be found on this very nice page maintained by William Cook.

Remark: SECs are often used as cutting planes in a branch-and-cut algorithm. In that case the separation problem is more difficult as it is applied to a fractional \(x\). Currently its fastest separation algorithm has a worst-case running time of \(O(nm + n^2 \log n)\) where \(m\) denotes the number of nonzero \(x\) in the fractional solution. In our case, using SECs as lazy constraints, the separation problem is applied to a binary \(x\). Although the separation problem becomes easier if SECs are used as lazy constraints, it does not mean that TSPs are solved more efficiently that way.